PLATO AND HIS THOUGHT

WHO WAS PLATO?

Plato was born in 428/7 or 424/3 BC to a scion of the Athenian aristocracy. His father, Ariston, was an alleged descendent of the Neleid dynasty which ruled Athens for two generations prior to the abolition of the monarchy and insitution of the perpetual archonship in the 11th century BC, who held a cleruchy (landholding) on the island of Aegina, settled by Athenians in 431 BC after the expulsion of the natives. Plato's mother was Perictione, a descendent of the archon Dropides, a relation and confidant of the great Athenian statesman Solon, and a niece to Critias, who emerged as a leading light among the Thirty Tyrants imposed by the Spartans in 404 BC following Athens' defeat in the Peloponnesian Wars. Her brother was Charmides, a ward and protégé of Critias, who was also active during this brief oligarchic period. Plato's two older brothers, Glaucon and Adeimantus, had been praised for their part in a battle near Megara, either in 424 or more likely 409, which saw one of the last Athenian land victories of the conflict. In addition, a sister, Potone, was the mother of Speusippus, Plato's eventual successor as scholarch of the Academy. Diogenes Laërtius [Lives of the Eminent Philosophers 3.4] suggests that Plato's given name was Aristocles.

Various legends became attached to Plato's birth and infancy. Apuleius, best known for his novel The Golden Ass, recorded a tradition which stated that he was born on the anniversary of Leto's appearance on Delos and was conceived through Perictione's receipt of a divine vision. Furthermore, Leto's son Apollo intervened to stymie Ariston's attempts to force himself upon Perictione. Ariston died shortly after Plato's birth and Perictione married her mother's brother Pyrilampes, a former associate of the strategos Pericles, giving him a son, Antiphon.

Diogenes informs us that the young Plato was afforded both an extensive physical and mental education, studying under one Dionysius and learning the art of wrestling from an Argive, also called Ariston, possibly competing in the discipline at the Isthmian Games. As a young man, he dabbled with poetry, with Diogenes citing an example dedicated to a certain Archeanassa of Colophon, described ("absurdly" in the opinion of modern philosopher Roger Scruton) as Plato's mistress, though destroyed all of his work after encountering Socrates, following his mentor into philosophy. Another possible female love of Plato was a certain Xanthippe (a namesake of Socrates' wife), whilst male favourites included his Syracusan associate Dion [Lives 3.30], as well as Alexis, Phaedrus [3.31] and Agathon [3.32]. Plato later contemplated a career in politics at the time that Athens was under the rule of the Thirty Tyrants, as he himself suggests in his Seventh Letter [324cd]: -

He quickly becomes disturbed by the carnage wrought by the tyrants and decides against further involvement in political life [324d-325a]: -

The tyrants were eventually ousted by another revolution, and Socrates was executed in 399 BC. Subsequently, having fallen in with Cratylus the Heraclitean and Hermogenes, a follower of Parmenides, in the wake of Socrates' death, Plato left Athens, reputedly at the age of 28, at first to go to Megara, where many of Socrates' former followers had settled at the home of the philosopher Euclides. It was around this time that Plato began writing his wide-ranging body of philosophical works, known as the Dialogues, the earliest of which heavily focus on Socrates as a protagonist. One of the most significant is the Apology, written shortly after Socrates' death.

After Megara, Plato is said to have ventured to Cyrene and Italy [3.6-7], visiting the mathematician Theodorus in Africa and two Pythagoreans, Philolaus and Eurytus, in the latter destination. Diogenes mentions a journey to Egypt to consult with "those who interpreted the will of the gods," though this tradition is problematic.

Plato returned to Athens in about 387 BC, founding the Akademia or Academy at a site which included a sacred grove of olive trees, which developed into the one of the ancient world's premier philosophical centres, and surviving for just over three centuries until its initial destruction by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 86 BC.

Among Plato's students at the Academy was Aristotle, who went on to become a polymathic scholar with a wide range of interests, whose influence rivals that of Plato himself. Notably, female students were admitted to the Academy: Axiothea of Phlius and Lasthaenia of Mantinea, the former at least customarily wearing men's garb [Lives 3.46], and the latter, described by Athenaeus of Naucratis [Deipnosophists 7.10] as "the Arcadian courtesan," becoming Speusippus' lover.

As a speaker, Plato is described as somewhat soft-voiced, which is contrasted to his stocky frame: a certain Timon, as noted by Diogenes [3.7], calls him "a big fish, but a sweet-voiced speaker, musical in prose as the cicada who, perched on the trees of Hecademus, pours forth a strain as delicate as a lily."

Plato's thinking continued to be influential, and the Academy was refounded in the early 5th century AD by the Neoplatonists. The new Academy was closed by the emperor Justinian in 529. Plato's philosophy would go on to influence Western and, to some extent, Islamic, thinkers of the Middle Ages and beyond. In particular, the cosmogony outlined in the Timaeus influenced Christian thinkers, in particular those of the disparate group of sects today known by the shorthand term Gnostics.

Plato's later career took in a number of further journeys to Sicily, where he had come into contact with members of the Pythagorean school, who followed and built upon the teachings of the 6th century Samian philosopher and mystic Pythagoras. Pythagorean ideas, particularly in the field of mathematics, would prove a major influence on Plato's later work, including the Timaeus. Probably through the Pythagoreans, Plato was also exposed to ideas derived from Orphism, a mystery school centred upon the person and supposed poems of the mythological Orpheus. His efforts to influence the political life of the Greek city of Syracuse in Sicily are dealt with elsewhere. His journeys to Sicily would have placed Plato in close proximity to the sphere of influence of the Carthaginians, rivals of the Greeks. It is quite possible that Plato drew on material of Carthaginian origin when describing the mysterious west in the dialogues.

He eventually died at an advanced age (usually estimated as his eighties), in around 348/347 BC. According to one tradition, his death took place on his 81st birthday, having apparently fulfilled his earlier desire to initiate contact with the magi. Upon his death, Phillip S. Horky relates: "the magoi sacrificed to Plato because he had completed the perfect number nine times nine," and later asks "why would members of the early Academy wish to emphasize the encounter between Plato on his deathbed and visiting 'barbaric' practitioners of wisdom from the east?" Horky concludes that these traditions originated with Plato's student and secretary Philip of Opus, and discusses convergences between Platonic and Zoroastrian philosophy.

PLATO'S DIALOGUES

In total, Plato is recognised as the author of 27 authentic dialogues, produced during a career lasting from between the death of Socrates in 399 BC and Plato's own death in 347. They are usually classified on stylistic grounds, with reference to ancient material referring to the order in which they were composed, into Early (or "Socratic"), Early-Transitional, Middle, Late-Transitional and Late. Thomas Brickhouse and Nicholas D. Smith provide the following classification (please note the order has been altered to reflect the position of the Protagoras and Gorgias at the end of the Early group and the relative order of the Middle dialogues, with further fine-tuning based on the work of T.H. Irwin): -

Plato's dialogues represent more than half a century of work on the part of one of western philosophy's most influential figures. In all likelihood, the earliest is the Apology, Plato's version of Socrates' pre-mortem cri de cœur, in which Plato's mentor defends his career in the face of the jury, as well as recording a speech made in the aftermath of the sentence. Socrates' final days are also covered in the Crito, Euthyphro and the later Phaedo. Plato's early dialogues, given the byname "Socratic" by Aristotle, "are generally regarded as the most reliable of the ancient sources on Socrates, and the character Socrates that we know through these writings is considered to be one of the greatest of the ancient philosophers." Xenophon also wrote an Apology, which also details Socrates' attempts to justify his actions to the jurors at his trial. The Crito details a discussion between Socrates and Crito - who has offered to finance Socrates' escape only to be rebuffed - on the subject of justice and injustice, whilst the Euthyphro represents a conversation on holiness between Socrates and the mantic prophet Euthyphro.

Irwin groups the Crito and Euthyphro with a number of similar "shorter dialogues on ethical topics." The Charmides takes place after Socrates' return from Potidaea. He joins Critias and Chaerephon, a friend of Socrates, at Taureas' palaestra. The eponymous Charmides, Plato's maternal uncle, is introduced as Critias' ward and a youth of rare beauty, prompting a discussion of the concept of σωφροσύνη (sophrosyne, loosely translated as "self-control"). Beauty is also the theme of the Hippias Major, which has Socrates and the Elean sophist Hippias attempting to define it. The Hippias Minor has Socrates visiting Hippias, who is a guest of Eudicus in Athens, and having considerable fun by undermining Hippias' beliefs about interpreting Homer's Iliad literally, by presenting Achilles, who claims to hate liars, a more cunning liar than Odysseus. The eponymous character of the Ion also admires Homer. This short dialogue has Socrates discuss the nature of musical, artistic and poetic inspiration with Ion, who, as a rhapsode by trade, possesses a skill which Socrates argues is no skill at all but the product of divine inspiration. The Laches is a discussion of various definitions of courage. Participants include the statesmen Laches and Nicias, Lysimachus, the son of Aristides the Just, along with his friend Melesias and son Aristides. The Lysis explores the nature of friendship and love and depicts a discussion between Socrates and four younger men, Ctesippus, Hippothales, Lysis and Menexenus. This Menexenus is most probably Socrates' companion in the dialogue of the same name, which takes the form of a funeral oration, which Socrates claims to have learned from Pericles' mistress, the intellectual Aspasia.

The Euthydemus, Protagoras and Gorgias represent a development to a more sophisticated level or argument. States Irwin: "[they] are more elaborate works on similar themes; they also record confrontations between Socrates and (roughly speaking) professional intellectuals concerned with philosophical topics. These interlocutors are sophists, orators, and eristics, rather than the philosophical nonspecialists who appear in group 1." The last two also mark the introduction of one of Plato's most novel innovations: his use of myth, either pre-existing or of his own devising, as a means to shed light on the subject of the discussion.

In the Euthydemus, Socrates tells Crito of discussions held between himself and the sophists Euthydemus and Dionysodorus. Like the Hippias Minor, Plato uses Socrates as a means to poke fun at the flaws of the sophists. Hippias returns as one of at least three sophists in the Protagoras. The discussion takes place at the home of the wealthy dynast Callias, with Socrates engaging in more serious discussion with the title character, another of the sophists. The Gorgias has Socrates discuss rhetoric with the sophist and rhetorician Gorgias, among others, at a dinner party.

The nature of virtue is explored in the Meno, which introduces metaphysical and epistemiological elements. The Cratylus has Socrates answering a query from Cratylus and Hermogenes on names, which is developed into a treatise on the true nature of sound and language, with naming compared to the work of an artist. The Symposium features Socrates at a gathering of friends, all of whom are challenged to give a speech on love. The Phaedo (which, as noted previously, features Socrates on his deathbed) provides a touching discussion on the nature of the soul and the afterlife, told to the eponym, Phaedo of Elis. The "metaphysical & epistemiological elements" developed in the preceding dialogues are examined in the Parmenides and Theaetetus. In the former, a young Socrates is depicted in the company of the Eleatics Parmenides and Zeno of Elea, with Parmenides inviting Socrates to shed more light on the nature of forms, and the Athenian describing the nature of madness, the soul and love (especially pederastic love). The Theaetetus, like the alleged Solonic material in the Critias [113b], is claimed to represent a written account of a dialogue between Socrates and the young mathematician Theaetetus on three definitions of knowledge.

Of the later dialogues, the Philebus has Socrates face off against the hedonist Philebus and Protarchus, whose oratory prowess has been honed in the school of sophistry. The Sophist and Statesman endeavour to define those two roles, as well as that of the philosopher and, like the Timaeus and Critias, do, to some extent, recall some of the material from the Republic. Conspicuous by his absence from the Sophist is Socrates: instead, the protagonist is the Eleatic Stranger, a visitor from Elea in southern Italy, who discusses the nature of sophistry with Theaetetus. The Eleatic Stranger again leads the discussion in the Statesman, where he is joined with another Socrates ("Socrates the Younger") and another mathematician, Theodorus. Socrates the philosopher is reduced to a minor role. Politics is also the major theme of Plato's two longest works, the Republic and the Laws.

In addition, Brickhouse and Smith list various dubia (The Minos, Theages, Cleitophon and First Alcibiades, as well as the Third Letter in some schemes), spuria and seventeen or eighteen epigrams attributed to Plato. Of the dubia, the Clitophon may have been envisaged as a prologue to the Republic, with the Minos serving in a similar capacity vis-à-vis the Laws, notwithstanding the possibility that the Minos is potentially of a significantly earlier date. A spurious work, the Epinomis, perhaps written by Plato's secretary Philip of Opus, is apparently meant as an appendix to the Laws. The First Alcibiades depicts Alcibiades as a young man who has alienated many of his acquaintances through his overbearing manner. The Theages features a discussion between Socrates, Demodocus and Demodocus' son Theages about Socrates' inner voice. Two further dialogues are counted among the spuria by Blockhouse and Smith. The Hipparchus, taking its name from the 6th century tyrant and son of Pisistratus who is discussed in the dialogue, is a discussion of greed. The Rival Lovers has Socrates intervene in a quarrel between two lovers, an older man with a love of wrestling and a more cultivated younger man. Additionally, Diogenes Laërtius lists ten further spuria, of which "[f]ive [...] are no longer extant: the Midon or Horse-breeder, Phaeacians, Chelidon, Seventh Day, and Epimenides [3.62]. Five others do exist: the Halcyon, Axiochus, Demodocus, Eryxias, and Sisyphus." Blockhouse and Smith add: "[t]o the ten Diogenes Laertius lists, we may uncontroversially add On Justice, On Virtue, and the Definitions, which was included in the medieval manuscripts of Plato's work, but not mentioned in antiquity."

Of Plato's letters, only the Seventh and possibly the Third are widely regarded as genuine. All but the Thirteenth are suggestive of a later date in the philosopher's career.

One of Plato's abiding themes is the concept of justice in an afterlife. Having experienced the inhumanity that certain members of the human race are capable of, Plato concludes that there must be life after death, with some form of judgement [Gorgias 523e-524a]. Though this is apparently in accordance with earlier beliefs, Plato differs in the fact that moral conduct and lifetimes of philosophical inquiry are the way to the Isles of the Blest [Gorgias 526b], rather than accidents of birth, gory deeds in wartime or, as in the case of Menelaus [Odyssey 4.561-569], by virtue of a spouse.

Corollary of this is an emphasis on maintaining the purity of the soul, which, like the body, is seen to be corruptible [Gorgias 524d-525a]. This concern for one's fate in the afterlife, developing from the promises of the Mystery Cults (such as the aforementioned Orphism), would prove influential to the more otherworldly elements of Christianity, in particular the group of sects known as "gnostics," some of which took Plato's ideas and developed them. It is germane to note here that early Christianity cross-fertilised with Neoplatonism, the tenets of which were developed by the philosopher Plotinus' interpretations of Plato's thought.

One of Plato's most important contributions to world thought is his "Theory of Forms," also known as the "Theory of Ideas." This notion posits an exemplar of various concepts, be they more or less abstract, existing outside of the material realm, whose manifestations in the realm of matter are imperfect reflections. Plato conceptualised their location as being in a ὑπερουράνιος τόπος, i.e. a "location beyond heaven" [Phaedrus 247bc]. In the Timaeus cosmogony, the forms originally appeared in the χώρα, an interval between being and not being.

THE ATLANTIS TEXTS - TEXTUAL HISTORY OF THE TIMAEUS-CRITIAS

THE RELEVANT SECTIONS OF THE TIMAEUS AND CRITIAS CAN BE PERUSED HERE.As noted, everything Plato wrote about the island civilisation of Atlantis is contained within two dialogues, the story being introduced in the Timaeus [21a-26d] and a detailed description of its political framework and history being furnished in the Critias. The dialogues Timaeus and Critias are believed to have been written in the first half of the 350s BC. It is generally (though not universally) accepted that the Timaeus was the earlier of the two. It is likely that these works were originally envisioned as forming two parts of a triptych, with a third dialogue, probably to be named the Hermocrates (after the third of Socrates' companions in the extant dialogues). However, the Critias was (perhaps by design) never finished and the "Hermocrates" was left unwritten. The dialogues form something of a sequel to and, in some ways, a discussion of one of Plato's major works, the Politeia or Republic, which outlines Plato's notions of the ideal constitution. This constitution is applied retrospectively to ancient Athens after Socrates, the protagonist of the Republic, expresses a desire to see how the state he described would fare in war. In Timaeus [19c], he says: -

Critias obliges, providing a description of the Athenians of a remote time and the prosecution of a defensive campaign against aggressive imperialists, a people from "beyond the pillars of Heracles" [Crit. 108e]. This was is portrayed as having occurred at a fabulously remote date, dated to 9000 years before the time of the Athenian statesman Solon [Crit. 111a, cf Tim. 23e], whose career dates to the early to mid 6th century BC. Critias has Solon's Egyptian informants explain that the war with the Atlanteans was forgotten by the Athenians after a global cataclysm which resulted in the destruction of Atlantis and caused severe damage to Athens [Crit. 109de], claiming the lives of most of the city's leaders and military personnel [Tim. 25d]. The reason why this glorious tale was unknown to the Athenians of Solon's day is put down to the repeated catastrophes which befell the globe during the intervening period, of which the Deucalionic flood was but the latest [Tim. 22cd; Crit. 109d, 111ab]. The exemplar of these disasters is the explanation of the Greek legend of Phaethon – which is said to be known, in some form, to the Egyptians also – which represents a destruction of life by means of fire. In the case of Phaethon, "the truth of it lies in the occurrence of a shifting of the bodies in the heavens which move round the earth, and a destruction of the things on the earth by fierce fire, which recurs at long intervals."

ANCIENT TRANSLATIONS OF THE TIMAEUS

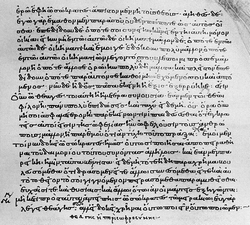

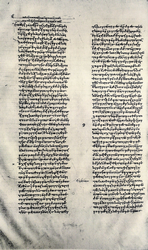

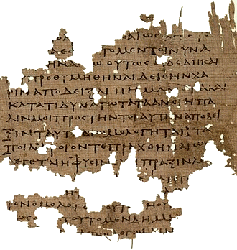

The Timaeus - most of which concerns the nature of the world and the universe, identifying a dichotomy between the physical and eternal realms - would become one of Plato's best-known and most influential works. It was partially translated by the great Roman orator Cicero [27d-47b] and translated again with a commentary by Calcidius [17a-53c]. Through these translations, the worldview developed in the text would prove influential to Carolingian intellectuals in the 9th century AD. A copy of such a provenance is included in the mid-9th century Leiden Corpus, with the earliest extant texts of all three versions all dating to around the same time. The earliest texts of the Critias, along with much of the remainder of Plato's work, were produced in the Byzantine Empire at around the turn of the 10th century AD: the oldest surviving manuscript, entitled B, was copied by a certain John the Calligrapher in 895 AD.

PLATO'S POLITICS

Of all Plato's interests, the one of paramount importance in the understanding of the Timaeus-Critias account of Athens and Atlantis is his political thinking. This is the main focus of his two longest works, the Republic and the Laws.

THE REPUBLIC

The Atlantis story is contextualised as an attempt on the part of Critias to provide a real-world exemplar of Socrates' heavenly city of Callipolis. This is found in the form of the forgotten "Ur-Athens" as Luc Brisson and F. Walter Meyerstein point out. The Atlantic island is introduced in the Timaeus as an enemy of this redoubtable ancient Athens and is expounded on at length in the Critias. Unfortunately, Critias breaks off just as Zeus is about to explain his resolve to devise a corrective punishment for the Atlanteans as a result of their excesses. The Timaeus takes up the story, noting the familiar cataclysmic destruction of the island and the simultaneous disaster overcoming the Athenian leading lights.

In the Republic, Plato, with a view to ensuring a happy coexistence for all citizens within his notional city state, develops an ideal system of government and outlines four forms of government which, in contrast, are imperfect. The ideal state is governed by phylakes ("rulers" or "guardians" - the term is used interchangeably to describe both the rulers and defenders of the city, with Plato stating that it would be most appropriate to denote the rulers as phylakes at 3.414-415, with the wider use of the phrase more consistent with its usage in the Timaeus and Critias), defended and administered by a warrior caste termed epikouroi ("auxillairies") and, under these and separated from them, are the polloi, the common people, broken down into husbandmen and artisans (two of the four classes which Strabo credits Ion with having created [8.7.1]), as well as merchants. This tripartite division is to be explained through a conceit of the stratification's being based on the different types of soul allocated to each of the classes. Basing this schema on myths such as that of Cadmus and the spartoi (derisively dismissed as a "Phoenician tale" at 3.414c, cf Laws 2.663e, where it is called a "Sidonian fairy-tale") and Hesiod's five ages (gold, silver, bronze, heroic and iron [8.547a]), Plato suggests that those born with souls of gold are to serve as the philosopher aristocracy, whilst silver souls are given to those whose calling is warfare. The possibility of meritocratic movement between the classes based on the specific abilities of an individual - both upwards and downwards - is mooted [3.415c]. The city's working class possess souls of brass and iron. Also pertinent is Plato's notion of three temperaments: λογιστικόν (logical, akin to that of the Greeks); θυμοειδές (spirited, akin to northern races such as the Thracians and Scythians); and ἐπιθυμητικόν (appetitive, akin to mercantile peoples such as the Phoenicians and Egyptians - as well as the Atlanteans).

The stages of the city's formation are developed in the earlier part of the text. Three of the groups dealt with - merchants, warriors and philosophers - are included in the introduction in the persons of the metic Cephalus, the martial Polemarchus, and Theophrastus, a sophist who is easily bested by Socrates in their exchange on the nature of justice. These discussions form a starting point for a detailed examination of various topics by Socrates and his interlocutors, Plato's brothers Glaucon and Adeimantus. Plato describes the community coming together, formed of people plying various trades [2.369-370], coming together to satisfy basic necessities, to which is added a mercantile dimension which allows the development of a taste for luxuries (a negative situation, as discussed also in the Laws [4.704d-705e]). Katie Shauberger terms this acquisitive nature "a sense-based reality." An unfortunate side-effect of this development is the production of conflict.

A class of people whose purpose is thus to defend, police and administer the city is then discussed, and this group, eventually labelled epikouroi, are, like the polloi, disallowed from political activity, though, unlike them, they are also unable to amass private wealth - indeed, even such basic rights as belonging to a nuclear family are barred. The epikouroi are to be trained to a specific curriculum and are subject to strict regulations to ensure their ability to carry out their functions. Like the polloi, the epikouroi exist within the realm of the senses, denying their chance to access "higher knowledge." The state's governance of the affairs of the epikouroi is similar to the situation in Sparta, a state which receives some muted praise from Plato [8.544c].

Finally, the city's absolute rulers, the phylakes, are introduced. As noted, the phylakes enjoy absolute power: the duties of the epikouroi are to pursue whatever conflicts or duties are deemed necessary by their rulers without recourse to a veto or a say of their own: Roy Owens characterises them, along with the polloi or common people, as an "oppressed class." Additionally, the phylakes must be at least 50 years of age (coincidentally or not, this is also the age at which the education of the epikouroi ceases) and - unsurprisingly, given Plato's own calling - are to be philosophers [2.376; 5.473]. Being dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge through higher forms of philosophical study, the phylakes render themselves immune to the temptations of the flesh and distractions which would lead to injustice.

Some of Plato's most radical ideas are based around the complete equality that women enjoy in exercising identical functions to men. In addition, neither the phylakes nor epikouroi are permitted to own property. In the case of the latter, their allocation of spouses is strictly regulated and children are brought up by the state. The state also exercises censorship: the work of Homer is among the literature which is to be proscribed. Instead, a new form of art extolling the virtues of the state is to be propounded.

The later part of the book discloses how the "aristocratic" or "monarchic" government by the golden-souled phylakes (henceforth "Platonic aristocracy," in contrast to the classical aristocracy based on an individual's social position at birth) devolves through stages via timocracy or timarchy (government based on honour, e.g. Sparta or Crete - Plato ascribes both good and bad features to this type of government), oligarchy and democracy to tyranny, the least desirable form of government. This is couched in terms of the sons of the preceding generation becoming corrupted and eroding the constitution of the state and involves a degeneration of the ruling element of the city through the hierarchy set up in the constitution of the Callipolitan state. First of all, the warriors become dominant, pursuing matters of honour rather than "good" governance, before the quest for wealth takes over. The next revolution sees a new constitution based on wealth. The downfall of this sees more unsavoury elements among the poorer people in society - characterised as κηφήν ("drones") - overthrow their rich masters and develop a democratic system [Republic 8.556]: -

The democracy causes the people to become dissolute pleasure seekers, mercurially moving from one interest to another. Eventually, an opportunist arises when further calls for increasing the financial burden on the rich appears. Originally promoting himself as the "protector" of the people and their ally, he eventually contrives to have a bodyguard allocated to him and eventually, the surfeit of freedom becomes the slavery of the state to this one man [Republic 8.566]: -

THE LAWS

In many respects, Plato's final work, the Laws, represents a disavowal of the ideas set out in the Republic and developed in Critias' description of the ancient Athenians in the Timaeus and Critias. This dialogue, the most lengthy in the Platonic canon despite its apparently remaining unfinished at Plato's death, takes place between the Cretan Cleinias, the Spartan Megillus and an Athenian Stranger. Though Aristotle [Politics 2.6] suggests that this is Socrates, a number of differences between the pair have been identified. The three meet on the road to a sanctuary of Zeus.

It begins by examining the laws of Sparta and Crete, touched upon in the Republic, which regards both states as combining good and bad principles in their constitutions. It goes on to develop the idea of a constitution aiming to promote the virtue and happiness of citizens. Coincidentally, the Cretans are planning to build a new city, Magnesia or Magnetes, on land long left fallow by the emigration of its prior inhabitants. The trio go on to draft the instruments by which the city will be organised and governed.

The population will be strictly regulated, being fixed at 5,040 households, each of which have two plots of land, one suburban and one rural. In contrast to the Republic, women remain second class citizens, though enjoying more of a say than contemporary Athenian women: they are allowed to participate in the decision-making process [5.814c] and are eligible to be called up for military service. Four classes are outlined, based on property ownership, similar to the Solonic settlement in Athens. Metics can only remain in Magnesia for a maximum of twenty years.

Politically, the ekklêsia ("assembly") is composed of all citizens who are serving or have served in the military. This body elects the civic officers and has legislative and judicial functions. The boulê ("council") is formed of 90 citizens from each of the four classes elected on an annual basis. Men over the age of 30 and women aged 40 and over are eligible. This body receives foreign ambassadors, as well as serving administrative functions such as calling and dissolving the ekklêsia. Another important group are the nomophylakes ("guardians of the laws"), 37 citizens aged at least 50 who serve from the time of their election until they turn 70. They have the power to revise laws and possess wide judicial functions. Another group, the nukterinos sullogos ("nocturnal council"), includes the ten oldest nomophylakes, as well as citizens who have served in other countries in a fact finding capacity, current and former supervisors of education, and other functionaries. The nature of this grouping, who oversee the re-education of errant citizens sentenced to five years' imprisonment for unintentional violations of religious laws, is debated.

One of the most enigmatic phrases in the Laws is the term "second-best city," which appears in relation to Magnesia in 5.739ab. The probability of this statement being an endorsement of the system outlined in the Republic - which would be the best of all - seems appealing, though it is not necessarily so: Chris Bobonich and Katherine Meadows suggest instead that the best city is "one in which there is, throughout the entire city, a community of property and of women and children."

PLATO ASSESSED IN ARISTOTLE'S POLITICS

Plato's disciple Aristotle also wrote a significant treatise on the subject of politics. After setting up his own school, the Lyceum, in the mid-330s BC, the Peripatetics were tasked with gathering evidence in the form of constitutions: some 158 constitutions of Greek states were collected, of which the only one to survive is that of Athens.

In his Politics, Aristotle reviews the nature of the differing proposals for and working models of political life in city states, providing a critique of Plato's Republic [2.1-6] and Laws [2.6]. Aristotle laments Plato's lack of detailed information on how to bring about some of his more radical proposals from the Republic, such as the holding of spouses and children in common, suggesting that such a state of affairs is contrary to the foundations of city state life, of which the most fundamental unit is that of the family [1.2, 3]. He finds the premise set out in the Republic impractical and denies it could ever be achieved in reality. Furthermore, Aristotle has misgivings about the caste-based constitution, which he sees as ripe for formenting rebellion among the two disenfranchised classes, as Plato himself notes [Republic 8], in discussing the downfall of the Callipolis. In both cases, Aristotle is cynical about the constitutions set out by Plato, which he regards as being poorly elucidated and overly restrictive.

PLATO'S RELEVANCE IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Does Plato's political thought deserve attention in the 21st century? I would argue that Plato is indeed relevant - and increasingly so in the fractious political climate which prevails across much of the globe at this time.

Plato's utopian leanings are evident from his work, with the Republic in particular proposing the ideal conditions for a state. These are unchanging and all-pervading, though not without social mobility based on merit. In particular, his concept of phylakes - the guardians of the state and its governing body - as well as his theory of the devolving of the ideal state through various stages to democracy (in the ancient Greek sense, rather than today's "representative" form) and eventually tyranny - find, I believe, close parallels in today's political discourse.

Nonetheless, despite his idealism - and it ought to be noted that, predictably, Plato's endeavours to put his theory into practice were stymied by that evidently flawed concept of human nature, which utopian thinkers often ignore - Plato also maintained that, in order to make a success of a political entity based upon the constitution he outlined, the state will need to control education - in particular, by the propagation of the "Noble Lie," which is, in his case, the concept of souls being associated with particular metals of varying value.