°Arcus°

Home » A journey to Atlantis

A JOURNEY TO ATLANTIS

"Listen then, Socrates, to a tale which, though passing strange, is yet wholly true, as Solon, the wisest of the Seven, once upon a time declared."

[Critias, in Tim. 20de].

IT ALL BEGINS WITH PLATO

Everything we have received from antiquity about Atlantis is contained in two dialogues by Plato, the Critias and, to a lesser extent, the Timaeus.

Every other reference we have is almost certainly derived ultimately from the authority of these two dialogues.

Plato and his thoughtWho was this Plato chap anyway? This page has a brief biography and introduces his dialogues, his political thought and adds a few notes on his relevance in the present day. |

Plato's mythsA look at how Plato makes use of "myths" in his dialogues, as well as providing a brief run-down of these particular tales. |

Plato's wordsTexts of Platonic myths in translation: from the Protagoras, Gorgias, Meno, Symposium, Phaedo, Republic, Phaedrus, Statesman, Laws - and, of course, the Timaeus and Critias. |

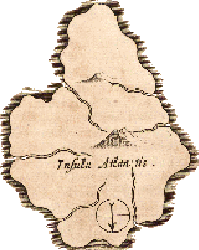

PLATO'S ATLANTIS: THE BASICS

A series of pages which seek to home in on Plato's conception of Atlantis. Was it real? Did Plato make it up? Where could it possibly be found? How big and powerful was Atlantis?

Also important is an understanding of the dialogues in which the tale was couched. Who were the speakers and what do we know about them?

SOME HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Examining the historical background to the Atlantis myth, with particular reference to ancient Athens and Egypt.

This section also includes a piece on the popular "Minoan hypothesis" which associates Atlantis with that great Bronze Age civilisation centred on Crete, as well as the notion that the "Sea Peoples" noted in Egyptian documents from the end of that period might be from some candidate for "the real Atlantis."

Atlantis, Greece and the lure of Egypt:For the ancient Greeks, the great civilisation of Egypt, with its storied history and hoary past, held an irresistible appeal. Both Solon and Plato were said to have visited. This page also seeks to answer the question of whether or not the "Sea Peoples" came from Atlantis. |

Thera, Crete and Atlantis:One of the more popular theories about Atlantis posits a connection with the eruption of Thera and the end of the Minoan civilisation, named for the famous King Minos, centred upon the island of Crete. But did the Greeks of Plato's time remember the Thera eruption? Does a misunderstanding or scribal error make the Minoan hypothesis more plausible? |

|

Truth, lies, Apaturia:What are the concepts muthos and lógos? What is truth? What were the significance of the Apaturia and Panathenaea festivals which feature in the dialogues? |

The Phaethon myth and ancient catastrophism:Plato states that Solon first heard of Atlantis from an ancient priest at Egyptian Saïs, though the philosopher himself held the Egyptians to be somewhat suspect as eyewitnesses. |

MOTIFS IN THE TIMAEUS-CRITIAS

A series of pages which seek to home in on Plato's conception of Atlantis. Was it real? Did Plato make it up? Where could it possibly be found? How big and powerful was Atlantis?

Also important is an understanding of the dialogues in which the tale was couched. Who were the speakers and what do we know about them?

The opposite continent:One of the more neglected themes dealt with in the Timaeus-Critas is Plato's innovative suggestion of a continental land mass existing beyond the Atlantic. This page looks at the etymological connection to Anaximander's ἄπειρον and the Aperaea of the Odyssey, before tracing precursors and analogues in the works of Herodorus, Theopompus and Plutarch and, moving beyond the Greek world, among the Persians, Babylonians, Indians and even the Norsemen! |

What is the significance of red, white and black?:Stones of these colours, says Plato, were used in buildings on the citadel at Atlantis. The colour theory of the Timaeus is invesigated, as well as the white and black horses in the myth of the chariot of the soul from the Phaedrus, before seeking precursors in ancient Uruk, among the early Indo-Europeans and Apuleius' description of Isis. |

|

Sacred springs:There are hot and cold springs at Atlantis and Troy. Similar springs appear elsewhere in Homer's works, as well as in Pomponius Mela (the Fortunate Isles), Pausanias (the Styx and Alyssus), and in the underworld according to Plutarch and Orphic sources. Also covered are the Asbama in Anatolia, the Illyrian "Land of Bliss" and the qrtj from which the Nile begins in Egyptian material. The possibility that Atlantis was a volcanic island is also considered. |

Twins in ancient Greek myth:Plato's depiction of five sets of twins being born to Poseidon and Cleito in Atlantis requires closer examination in light of myths involving twins in wider Greek mythology. Featured on this page are the Aloidai, Aeolus and Boeotus, Chrysaor and Pegasus, Lycus and Nyctimus, and the Moliones. |

ATLANTIS BEYOND PLATO?

This section investigates claims that Atlantis was known independently of Plato's work, both within ancient Greece and without.

A number of theories - many rather on the fringe of the argument - are covered here.

Who else wrote about Atlantis?:A variety of writers other than Plato are said to have (more or less independently) made references to Atlantis. This essay features those few which are most commonly cited, namely Hesiod, Herodotus, Hellanicus of Lesbos, Aristotle, Theophrastus, Theopompus, Crantor, "Marcellus," and Claudius Aelianus, as well as some supposed Indian references to Atlantis. |

Atlanteans in Africa:A people known as Atlantes or Atlanteans appear in north-western Africa in the works of Herodotus and, alongside Amazons and Gorgons, in Dionysius Skytobrachion. |

|

Was Thoth an Atlantean and other Egyptian matters:Addressing a number of dubious claims that Atlantis was the precursor civilisation of pharaonic Egypt, including Thoth as an Atlantean (obviously), alongside a supposed western origin for the Egyptians in Diodorus Siculus, Laurence A. Waddell on Menes' western expedition, Carleton S. Coon's description of Osiris' homeland and the Auriteans. |

Atlantis and the druids?:Some have claimed that a reference to Gaulish druids' origin stories appearing works by Timagenes and Julius Caesar refer to the destruction of Atlantis. |