SUPER ZEN BROS.: FRISLANDA AND OTHER ISLANDS

INTRODUCTION

In 1558, a short treatise was published in Venice, written by the local dignitary Nicolò Zen (or Zeno), which purpoted to detail an expedition to the far north made by his forebears Nicolò and Antonio in the early 1380s. The story begins with Nicolò journeying north with the intention of visiting England and Flanders only to be caught up in a storm and blown off course much further north, coming adrift on an island named Frisland or Frislanda, where he comes into contact with a mysterious figure called Zichmni, the ruler of the islands of Porlanda nearby, as well as the Duke of Sorand or Sorano (which is said to be "over against Scotland"). Nicolò joins forces with Zichmni and thus begins a long association between Nicolò (and Antonio, who joins him in the north later). Zichmni employs the shipwrecked Venetian as his Admiral, whereupon they conquer seven islands near Estland (possibly Shetland). Nicolò, installed in a garrison on Bres, one of the conquered islands, then proceeds to the monastery near the church of St. Thomas on Engroneland - which would appear to be Greenland where it not for the presence of volcanoes and hot springs, which, rather, recommend Iceland (Andrea di Robilant suggests it was the monastery of Thikkvabaerklaustur) as part of a quest to explore the great northern ocean. The severe cold causes him to fall gravely ill and, having returned to Frislanda, he dies, being replaced as Admiral by his brother Antonio.

Subsequently, Antonio is dispatched westwards in response to the return of a fisherman to Frislanda. This fellow claimed to have spent the last 26 years in to lands in the far west, the first of which was Estotiland. The people of Estotiland – who seemed of European stock - traded with Greenland and possessed books in Latin, though were unable to read them. Their language was unlike Norse, suggesting perhaps that Estotiland is a late revivification of the Norse legend of Írland hið mikla. From there, the fisherman states that he went southwards to another land, Drogeo, which was populated by cannibals.

Antonio and Zichmni then mount an expedition to seek these islands but come to another instead, Icaria. Now, Icaria seems to genuinely belong to the realm of fantasy. It takes its name, of course, from the ill-starred Greek youth Icarus, here transmuted into an Atlantic seafarer, with his father Daedalus, bizarrely, made a king of Scotland, thus rendering this famed mythological Athenian craftsman the second oddest claimant after Ugandan tyrant Idi Amin. The expedition eventually results in the plantation of a colony on an unknown land, which is named Trin. Antonio returns home, whilst Zichmni travels on.

The narrative has been the subject of much debate as to its historicity, with a number of writers, most recently Andrea di Robilant, providing ample discussions of these debates. The most common candidate put forward as Zichmni is Sir Henry Sinclair of Rosslyn, a Scottish nobleman and the contemporary Earl of Orkney. Di Robilant and Raymond H. Ramsay put forward plausible reasons for accepting the identification, which was earlier proffered by R.H. Major, the legend's Victorian champion. That said, opponents of the voyages' historicity suggest that Nicolò made up the story wholesale, and suspect that this may have been for reasons of national pride: if (please note, "if") Trin is intended to be in the Americas, Nicolò is implying that that continent was discovered by a Venetian prior to the expeditions of Christopher Columbus, who hailed from Venice's great rival and enemy Genoa.

FRISLANDA BEFORE 1558

Frislanda was not an invention by the younger Nicolò Zen: islands with similar names were appearing on maps from the 14th century onwards. Even earlier, Muḥammad al-Idrīsī placed an island named R.slānda in the Baḥr al-Muẓlim which may be Frislanda. An Insula frixiland appears between Scotland and the Insula orchinia on Angelino Dulcert's 1339 chart, with the Pizigani brothers placing an Insula fislanda in the same location. Abraham Cresques' Catalan Atlas of 1375 features and Illa de frillanda, and both he and Dulcert mention that the Christian inhabitants of the place speak a Norse dialect. The "Columbus Map" features Frixlanda, while the Cantino Planisphere of 1502 places Frislanda north of the Orkneys and east-north-east of Illanda (Iceland), with the Ilhas de fogo ("Islands of fire") immediately south of its southwestern point. These can perhaps be associated with an island placed between Islant and Gruenlant by Johann Ruysch, who states that this island was totally destroyed in what seems to have been a volcanic event in 1456.

An island with a number of similarities to Zen's Frislanda, named Fixlanda (which appears to be Iceland), appears on a Catalan map dating from c.1480, which is currently housed in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan. Fixlanda also appears on a chart produced by the Majorcan Mateo Prunes which appeared in 1559, a year after the Zeno map, sharing a good number of topographic names in common with the Zen map. Additionally, the "Paris Map," dating from the 1490s and currently located in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, places an island named Frixlanda to the west of Ireland. In the words of Monique Mund-Dopchie: -

Furthermore, Frislanda may have had no less esteemed a visitor than Columbus himself: in 1477, according to a letter quoted by his son Ferdinand, the Geonese: -

On a number of maps - the Catalan map of c.1480 cited by William Babcock and maps by Mateo Prunes (1553) and Joan Rizo Oliva (1555) - toponyms within and close to the island are included, a number of which also appear on the Zen chart: -

| Catalan map (1480) | Prunes (1553) | Oliva (1555) | Zen (1558) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixland | Fixland | Fixlanda | Frisland |

| Aqua | Aqua | Aqua | Aqua |

| Compa | Conipa | Canfei? | Compa |

| C. Deruya | C. Duiya | C. Dereia | C. Deria |

| Dorafais | Dorafais | Darafei | Doffais |

| Ferou? | Foraxi | Sorari | Forali |

| Godmech | Godinech | Godine | Godmec |

| Lauina | Lauina | [L]auina | Vena |

| Ille neonie | Neome | ||

| Porlanda | Porlanda | Porlanda | Porlanda |

| Radeal | Labeal | Radeal | Rodea |

| Solanda | Solanda | Soranda | Sorand |

In these latter instances, Frislanda is most likely Iceland, which did historically have trading links with Bristol. By 1477, however, a change in the policy of the rulers of Iceland led to Bristol's being frozen out of this trade in favour of the Hanseatic League. According to Barbara Freitag: -

As a result of this exclusion, Bristol merchants sought to open up new trade routes, sending expeditions in search of the mythical island of Hy Brasil off the western coast of Ireland and culminating in the commissioning of another Venetian, John Cabot, who made several voyages to Newfoundland in the late 1490s. The presence of fishing fleets on the Grand Banks off Newfoundland could provide a context for the fisherman's tale of Estotiland and Drogeo in the Zen narrative.

It becomes apparent that Nicolò the younger, as de Robilant argues forcefully, is not making up his account wholesale, but is working with previous material. However, the bulk of that material is most certainly not of a 14th century, but a mid-to-late-15th and early 16th century provenance. Nevertheless, despite the nature of the younger Nicolò's interpretation, the possibility of Venetians in the far north during the later 14th century is not too remote: Venice had trading relations with England and Flanders during that century.

CLIMATE CHANGE

The possibility of the elder Niccolò's encountering stormy conditions in the North Sea region is not unlikely: climatologically, the latter part of the 14th century is at the cusp of the change from the Medieval Warm Period to the cooler Little Ice Age and the period was marked by a number of major flooding events throughout the North Sea. In the Low Countries, the remnants of the ancient dune systems which had been the major bulwark against the sea were severely compromised in a series of devastating floods:

The North Frisian island of Strand, eventually smashed to pieces as a result of the Burchardi flood in October 1634, was inundated in Saint Marcellus' flood, a.k.a. the Grote Mandrenke of January 1362, resulting in the loss of the major settlement of Rungholt, whilst in England Dunwich and Ravenser Odd were abandoned during the same timeframe. The Saint Vincent flood of 1393 and first Saint Elisabeth flood of 1404 followed as the climate continued to fluctuate. Flanders, meanwhile, was wracked by the Ghent Revolt between 1379 and 1385, though a policy of consolidating the dune systems, with well-funded flood management and drainage policies in place by 1400, suffered, neighbouring Zeeland was worse hit, losing a number of settlements in the period of interest: -

THE FAROE ISLANDS

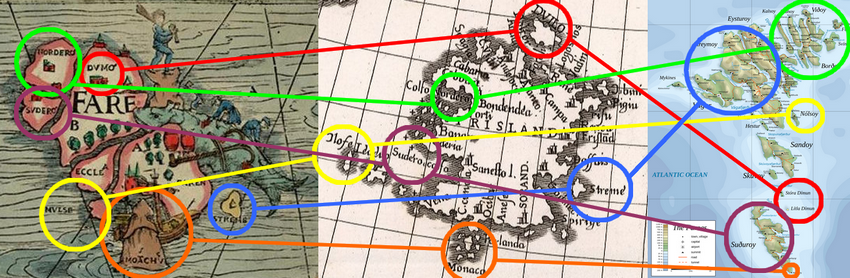

The Faroe Islands, rather than Iceland, are conspicuously absent from the Zen map, and, as such, are most likely the Frislanda of the Zen account. A number of places which are absent from the earlier charts of Fixland can be located on this archipelago, in some instances in locations comparable to those shown on Olaus Magnus'Carta Marina of 1539: -

| Carta Marina (1539) | Zen (1558) | Modern name | |

|---|---|---|---|

|  | ||

| Dumo' | Duilo | Dímun | Dímun |

| Moãchus | Monaco | Munkurin | Munken |

| Mulse | Ilose | Nólsoy | Nolsø |

| Nordero' | Golfo Nordei* | Norðoyar | Norderøerne |

| Streme | Streme' | Streymoy | Strømø |

| Sudero' | Sudero golfo | Suðuroy | Suderø |

*Golfo Nordei also appears as Golfo Bracir, which may be associated with the legendary Hy Brasil, as well as the Ilhas de fogo of the Cantino Planisphere.

A comparison between the Faroes in the Carta Marina (left) and a modern map (right) with Frisland in the Zen map (centre).

While some of these identifications must needs remain tentative, primarily due to the maps' failure to reflect the reality of their locations, a number of other Faroese locations can also be gleaned on the Zen map: -

| Zen (1558) |  |  |

|---|---|---|

| Andefort | Oyndarfjørður | Andefjord |

| Bondendea | Kirkjubøur? | Kirkebø? |

| Frislãd | Tórshavn | Thorshavn |

| Ocibar | Víkarbyrgi? | Vigerbirge? |

| Vadin | Viðoy | Viderø |

Furthermore, a number of other placenames from the Zen map's Frislanda also bear similarities with toponyms on its Islanda, placed in the conventional location of Iceland (though with a number of islands where the eastern portion of Iceland ought to be, presumably due to the further confusion of Islanda with Estland/Shetland): -

| Islanda | Frislanda |

|---|---|

| Aneford | Andeford |

| Cenesol | Sanestol |

| Floguscer | Logosthos |

| Olensis | Alanco |

| Valen | Vadim |

| Votrabor | Ocibar |

FRISLANDA AND THE FRISIANS

While it is not so great a stretch to imagine that the name of Frislanda may come from a garbled transmission of the name of the Faroes, the name does evoke that of the Frisian people, a proud, free race of people who, then as now, dwelt along the North Sea coasts of the modern Netherlands, Germany and Denmark - and formerly, according to traditional sources, in the Faroes themselves, primarily at Akraberg in the far south of the archipelago, opposite the aforementioned Munkurin.

These Faroese sources tell us that this group of Frisians arrived some time after the Northmen, thus after around the timeframe of AD 825-900, and drove out the pirates who formerly dwelt in the southern end of Suðuroy. They remained heathens during their time on the island and interacted but little with their neighbours, living by fishing and occasional pirate raids of their own. They eventually fell victim to the Black Death, which ravaged Europe between 1349 and 1350, though the details are murky. Needless to say, at the time when Nicolò and Antonio Zen were in the islands, their legacy would still be fresh in the memory of the older folks dwelling there, particularly on Suðuroy (which must surely be the location of Zichmni's holdings, Porlanda and Sorand both being placed on the map in the extreme south of Frislanda.

An earlier group, the Frisii, were known to the Romans, serving as laeti in Britain and Flanders at around AD 296. During the fourth century, their presence is denoted by the so-called terp Tritzum, particularly prevalent in Flanders and, perhaps significantly, Kent. During that period, however, sea level instability led to a decline in the population of the Frisian coast, with new immigrants coming from further east during the fifth century. These "new Frisians," kinsmen of the Angles and Saxons with whom they would migrate to Britain during the post-Roman uphevals in Europe, make their earliest appearance in the poetry of their insular kinsmen, particularly in the famous Bēowulf, which refers to a fight at Finnsburh involving Frisians, as well as a fragmentary text on the same topic.

According to these texts, the Danish prince Hnæf Hocing is visiting the Frisian ruler Finn Folcwalding at the latter's stronghold on one of the Frisian islands. Finn was likely his brother-in-law, being married to Hnæf's sister Hildeburh. However, a battle breaks out and both men are slain. Among Hnæf's company is one Hengest, an adventurer, while the cause of the fight may be the interference of eotenas among the Frisians. The eotenas are likely giants, which is quite apt given the imposing physique of many modern Frisians, as well as those in Faroese legend, though they could also be Jutes.

Eventually (if the two are one and the same), Hengest - or Hengist - would become the magister militum of the British overking Vortigern during the middle of the fifth century. The Historia Brittonum mentions a part of his plan to counteract the raids of the Picts and Scots from the north by dispatching his "sons" Octha and Ebissa on raids against them, in forty ships, in which: -

The "Fresic" sea, of course, suggests Frisians, and Frisian historians, following on from the publishing of the Zen narrative, provided an origin tale for these Frisians of the north, in the form of men under the command of one Taco or Tacco, a captain in service to Hengist, who founded a colony on the Faroes, serving as its first magistrate. He is said to have died in AD 536.

Meanwhile, back on the continent, the Frisians were expanding westwards, setting up an eventual reckoning with the Franks, emerging as the leading power in central Europe. By the 7th century, the Frisians held lands as far west as Dorestad and at least some of their number were under a king with a royal mint: Audwulf, who is attested as far as England. About half a century later, St. Wilfrid, exiled from his native Northumbria, found a safe haven at the court of Audwulf's successor Aldgisl, who protected him at great risk from Frankish plots to have him dealt with. However, while Aldgisl was sympathetic to Christianity, his probable son and successor Redbad was ill-disposed to the faith: after being beaten in battle at Dorestad by the Frankish major domo Pepin of Herstal in 689, he suffered significant reverses, leading at one point in 697 to his flight to Heligoland. The next century saw him back on the front foot, scoring a major victory over Pepin's successor Charles Martel at Cologne in 716.

Three years later, he was dead, and his successor Popo would suffer a decisive defeat at the Boarn in 734 when Charles Martel exacted his bitter revenge on the Frisians. Uprisings followed, including one at Dokkum in 754, which claimed the life of St. Boniface, with more significant actions occasioned by Charlemagne's invasion of Saxony in 772/3. The Frisian leader of the time, another Redbad, joined the Saxons in revolt, but was defeated and forced to flee to his Danish ally Haraldr. An uprising by the noblemen Unno and Eilrad in 793 was similarly put down.

These setbacks saw the Frisians migrate to the relative safety of islands in Denmark's orbit, which would eventually be the germ of the modern Nordfriesland. Others may have filtered further northward, perhaps to the Faroes, where they would have arrived at about the same time that the Northman Grímur Kamban was setting up home at in Funningur in the far north of the archipelago. In about AD 1040, another Frisian expedition to the north is recorded by Adam of Bremen. It is this notice which apparently gives the most commonly-held date for the Frisian occupation of Akraberg, notwithstanding the fact that these intrepid mariners were no heathens but good Christians. Other Frisians may have sought refuge on the islands after 1252, when a force led by Sikke Sjaardema defeated and killed King Abel of Denmark at Husum Bridge near Eiderstedt.

Probably the best-known intervention by these Frisians in Faroese history comes towards the end of their time on the islands as a distinct group. During the first years of the 14th century, Erlendur, a somewhat overbearing Norwegian, served as bishop and, as part of his legacy, he ordered the building of the cathedral of St. Magnus at Kirkjubøur, leading to further taxation on an already hard-pressed local population. His strategy appeared to be playing northerner off against southerner: those south of the mountain of Hórisgötu rose in rebellion, but were defeated by the northerners in a bloody encounter at Mannafelsdalur near Kaldbaksbotnur in southern Streymoy.

Undeterred, the southerners made plans to continue the fight. This time, they called upon bondin í Akrabyrgi, one of the few remaining Frisians. His name was possibly Hergeir and he had eight stout sons. The blood of the fallen of Mannafelsdalur was avenged the following year at Kollafjørdur and the victorious rebels laid siege to Kirkjubøur. The bondin í Akrabyrgi did not share his neighbours' hesitancy at attacking the holy ground on which the cathedral was being erected and prevented Erlendur and his servant "Mús" from escaping.

However, thirteen households at Akraberg dwindled to one in the wake of the Black Death and the two sons of the survivor (who is often confused with bondin í Akrabyrgi) moved to nearby Sumba, where they became Christian and married into the local population. Their new homes were the farmsteads of Hørg (interestingly, hǫrgr is an Old Norse term for an outdoor heathen sanctuary) and Laðangarður, places where subsequent generations would reside and maintain the legendary Frisian height and strength into the 17th century.

The paterfamilias is recorded as being one Regin í Hørg, who had a son, Jenís Reginsson í Laðangarði. His grandson was Jenís Símunarsson í Laðangarði, the father of Sterka Marjun, who married Símun í Nederhúsum without Jenís' consent and moved to Kálgarður, before receiving Hørg as a belated dowry. Marjun was the mother of the four Hargabrøðinir - Niclas, Jógvan, and the twins Ísak and Peter - whose deeds include the defeat of a group of Irish or Turkish pirates in around 1628 at Nes-Hvalba (that year also saw pirates wrecked on Sumbiarhólmur with one survivor), thus providing an apt end for the career of these latter-day Frisians. Jenís Símunarsson was also the father of Símun, whose son, also called Símun, moved to Kirkjubøur in 1618 or 1619.

The Frisian raiders are remembered today in the Faroes, as well as Iceland, where a children's song, Frísa Vísa, details their raiding for women.

THE STRANGE AFTERLIFE OF FRISLANDA

Once the cat, so to speak, was out of the bag with the publication of the Zen account, Frislanda was, for about a century, quite the regular feature on the various beautiful world maps of this great age of cartographic enterprise. Additionally, legends came to associate the place with the forebears of the Early Modern nation states of Europe, in particular the Dutch Republic (as can be seen in the patriotic accounts of the early Frisians we have already mentioned) and the rising power of England.

Once more, that great Renaissance man Dr. John Dee is intimately involved in advancing English claims to Frisland, claiming an association with both the legendary King Arthur and the Welsh prince Madoc. Two missives from Dee's voluminous correspondence make mention of the place, the first dating to Thursday 28th November 1577 (in which Dee records his having "declared to the Quene her title to Greenland, Estetiland, and Friseland"), the second from Monday 30th June 1578 (recalling "that Kyng Arthur and King Maty, both of them, did conquier Gelindia, lately called Friseland."). Sir Martin Frobisher's pilot George Best produced a chart of the islands of Arctic Canada in his account of the expeditions, which puts "West Ingland/Olde West Friseland" to the southwest of Iceland, directly east of the straits Frobisher and his men explored. Frobisher's Frislanda was almost certainly a mistaken Cape Farewell in Greenland, and it was Frobisher's three voyages which laid the foundations for another phantom island in the region, namely Buss Island.

Lastly, mention must be made of a curious account of the island's demise, which appears in the diaries of the Swedish naturalist and traveller Pehr Kalm, in which the author remarks on recent tales of the region received by his correspondent Dr. Mortimer from an assortment of sea-dogs. On the 18th May 1748, under the heading Friesland nu förloradt ("Friesland now lost"), Kalm writes: -

AMERICA?

Probably the most pervasive legacy of the Zen voyages is the notion that Sir Henry Sinclair was active in the Americas a century prior to Columbus and his contemporaries. Leaving aside the rather bizarre notions about Templar treasure and the Westford Knight for now, I will satisfy myself by saying that this theory is based on a number of assumptions, some of which the text itself mitigates against.

Add to this the confused geography of the document itself - Iceland as Shetland and Greenland as Iceland - and one is led to wonder how anyone can with confidence state that Zichmni - be he Sir Henry Sinclair or no - went any further than Greenland.